A Reviewing Gimmick

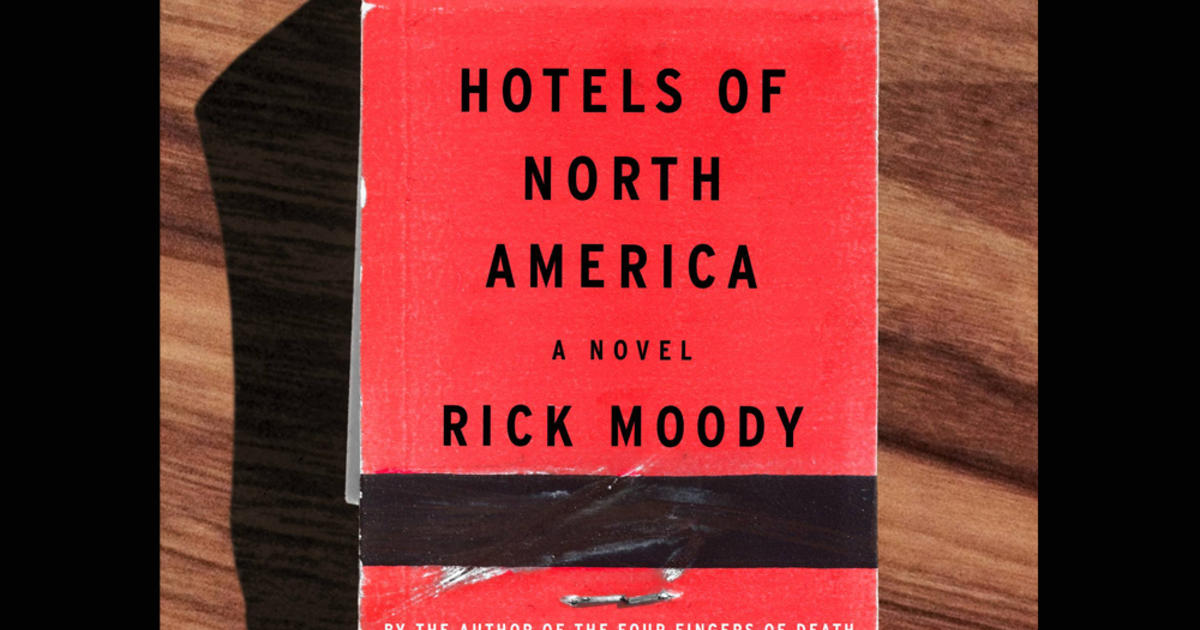

Review of: Hotels of North America, Rick Moody

Published in 2015, Moody’s book reads like the prototypical gimmicky novels that began trying to capture something about the Internet, and the strange new kinds of writing appearing on there. Our protagonist, Reginald Edward Morse, or R.E. Morse, or Remorse if you want to be as on the nose about it as Moody wants you to be, reviews hotels he’s stayed at (and doesn’t actually confine himself to North America). In my most generous reading, this book has a lot to say about the ways that even places where we exist transiently, those that by definition are only meant to be lived in for the short-term, leave long-lasting impressions on us. Hotels become the sets to the staging of our lives, and then the internet the staging of that extended performance.

The most compelling passage, to me, took that staging quite literally (forgive the lengthy blockquote, I checked this one out from the library and I’m considering this my archive of the one beautiful bit of the book):

“There was a very long corridor in the Davenport, that is true, but it was nothing compared to its Hall of the Doges…K. was unable not to dance across it. K. was a dancer as a young person, and she can still jump pretty high, and even though she has a few injuries of the sort that a person is liable to have when approaching true middle age, she just threw her jacket, a hoodie of some kind, on the floor of the entirely empty Hall of the Doges and began dancing into the center of the room, irrepressibly. Did I knew yet that this moment would describe everything we were going to be, the kind of people who would find it important to dance in hotels and especially to dance in hotels when otherwise besieged by the worst circumstances?

“[…] How long would they allow us to rehearse this dance? I personally know enough about Terpsichore to understand that diagonals are the most exciting shapes in a dance, how the dance starts at the back corner and moves forward toward the audience along diagonals, and I was an audience of one, and K. started from the back corner, and we had had our hard times, which I don’t need to enumerate here, but now we were here in the Hall of the Doges, and Snowy Owl was coming from that corner, on a diagonal, just like in one of those spectacular ballets where there is a princess and a frog, there is a history of the German peoples, or someone is a swan, and there are a dozen fifteen-year-olds whose toes are all bleeding as they do their extraordinary leaps, and it was all exactly like that, and I was worried about security coming to tell us that our stay was terminated in this hotel that was too good for us, but I was also worried about the dance ending, worried about the time after the dance, when the moment that had brought it about would begin to slip away” (86-87)

It's one of the few hotels he is willing to rate 5 stars, though as with all of his reviews it seems like less the hotel and more the memory he is rating. And this was one of those rare passages that I have to believe is what we read literature for, because someone puts into words something that you weren’t sure you could describe for yourself. I have the most clear memory of being in high school, on a trip to Paris. And even now I forget which museum of all the many museums we visited that we were in, but it was afternoon, and light was coming through the large leaded glass windows into the gorgeous space that was empty save for the architecture and ceiling and parquet floor, perhaps an event space for marriages like the Hall of Doges is used for. And our feet were tired from days of touring, and my friend sat down, but I couldn’t help but leap across that space, moved because I was young and in Paris and seeing more art than I’ve ever seen since, and just felt the effusive power a space with a good floor would command of my dancer’s body. I don’t have that dancer’s body anymore, but I feel that passion, and I felt it rise up again in this description of K., perhaps Terpsichore herself embodied, “irrepressibly” moving. The double negatives do a lot of heavy lifting here; it’s not that she danced, it’s that she couldn’t not, such was the need. It’s a feeling hard to capture, and Moody’s prose here deftly conjures it up.

Nothing in the rest of the novel could live up to this passage, and I certainly couldn’t bring myself to do more than skim the aggressively postmodern afterword. I’m sure it read differently in 2015, but I can no longer abide by internet novels that playact at the internet. The various reviews are supposed to convey something of place and space and how humans occupy it, but in a novel so intent on laying on thick the metafictional techniques, what might really be interesting to address as a theme—the impulse to review online—isn’t taken up to my satisfaction. Embarrassingly crafted usernames read as cringe when they are brought into these reviews by R. E. Morse, who is responding to comment sections we aren’t privy to. Either I’m supposed to believe that our protagonist writes long memoir-esque passages masquerading as reviews on what is really just a soapbox for him in which he is blind to the real use of the site, or that he is actually deeply invested in the site. I don’t think it can be both, yet Moody tries to make it happen. Either you lean into the fact that this is a stylistic constraint and keep it bare bones to approximate classical novelistic prose, or you give into the gimmick of replicating more of the site, which would involve much more design work, or more with comments, or anything to show the R.E. Morse actually knows anything at all about the internet. Moody isn’t pushing the bounds of the novel, as the jacket blurb suggest. He couldn’t push it far enough to do anything interesting with the form.